This is the second part of my worldbuilding efforts. As I explained last time, I’m using Richard Baker’s excellent World Builder’s Guidebook to generate much of my world randomly. So far, my world is a flat plane, roughly twice the size of Earth in terms of surface area, with one Asia-sized continent and a bunch of archipelagos. It’s a warm world – areas that would be temperate are subtropical, for example – and there’s limited seasonal variation. Oh, and there are three ‘world hooks’: my world has Arabian and Renaissance influences, and magic doesn’t work as normal on other worlds. However, I have yet to figure all of this out yet.

In this post, I am going to focus on largest landmass and add more detail. At the moment, I have a rough sense of coastline, climate bands, and mountain ranges, but I don’t have rivers, lakes, or terrain. I did think this post would focus more on human geography – kingdoms etc – but that will probably be the focus of Part 3.

Side note: flat worlds

The deeper I go into this, the more I realize that flat worlds require us to suspend a lot of disbelief. Gravity, tectonic plates, atmosphere, seasons: none of it makes sense with a flat earth model. I highly recommend Artifexian’s videos on the subject (see below).

To that end, we need to embrace the fantasy. Clearly, for this world to exist, there must be some kind of divine intervention at work, or a similar metaphysical force. Some D&D players hate this kind of hand-waving. For the purposes of this post, it’s a means to an end.

Also, just to be crystal clear: I am not a flat Earther. The Earth is round. It’s 2021, and I really shouldn’t have to say that.

Landforms

I have a good idea of where my mountain systems belong thanks to my plate tectonics. There is chain of low mountains running to parallel to the west coast, bounded to the east by a belt of foothills.

I generate some more hill systems, as well as some depressions, gorges, and escarpments. Spaces without hills or mountains can be considered plains for now, although they may become forests, lakes, or deserts later.

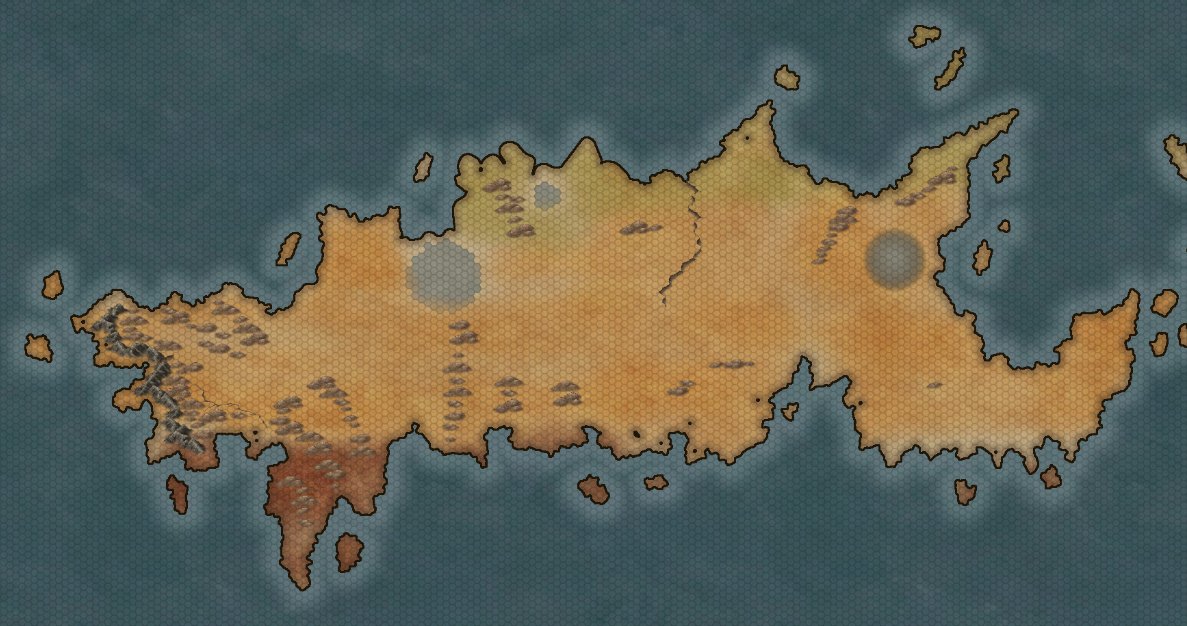

The result so far:

(I should add: I’m using Inkarnate to make these maps. There are other map-making sites, but Inkarnate is my favourite and very easy to use.)

Climate and weather

I determined in my previous post that this world is warmer than ours. Based on its position, the large continent is super tropical (ie, hotter than tropical) at its southernmost point, subtropical in its northern reaches, and tropical in the middle.

If we are going to look at climate, we also need to look at wind patterns. On Earth, wind patterns generally run clockwise in the northern hemisphere and anticlockwise in the southern hemisphere. If winds come off the ocean, they are humid; if they come off a landmass, they are arid. All in all, it looks much like the image below (credit: Wikipedia).

I have made my head hurt trying to figure out how this would work on a flat world, so I have decided to keep things simple and follow a vaguely Earth-like climate model (albeit warmed up), regardless of whether it makes sense from first principles. To that end, I envisage a continent that is largely arid in the centre, humid on its southern peninsula, and humid on the northwest coast. Maybe it’s not perfectly realistic, but it works for me.

Placing terrain

Baker’s method is based on two things: climate band (arctic, temperate, tropical, etc) and the type of wind (humid or arid). He suggests dividing each region into quadrants and each quadrant into terrain areas of random sizes. This is more or less what I did. There are random tables for determining the terrain type based on climate and humidity, but I used a bit of human judgement as well. Swamp, for example, doesn’t occur in mountainous areas.

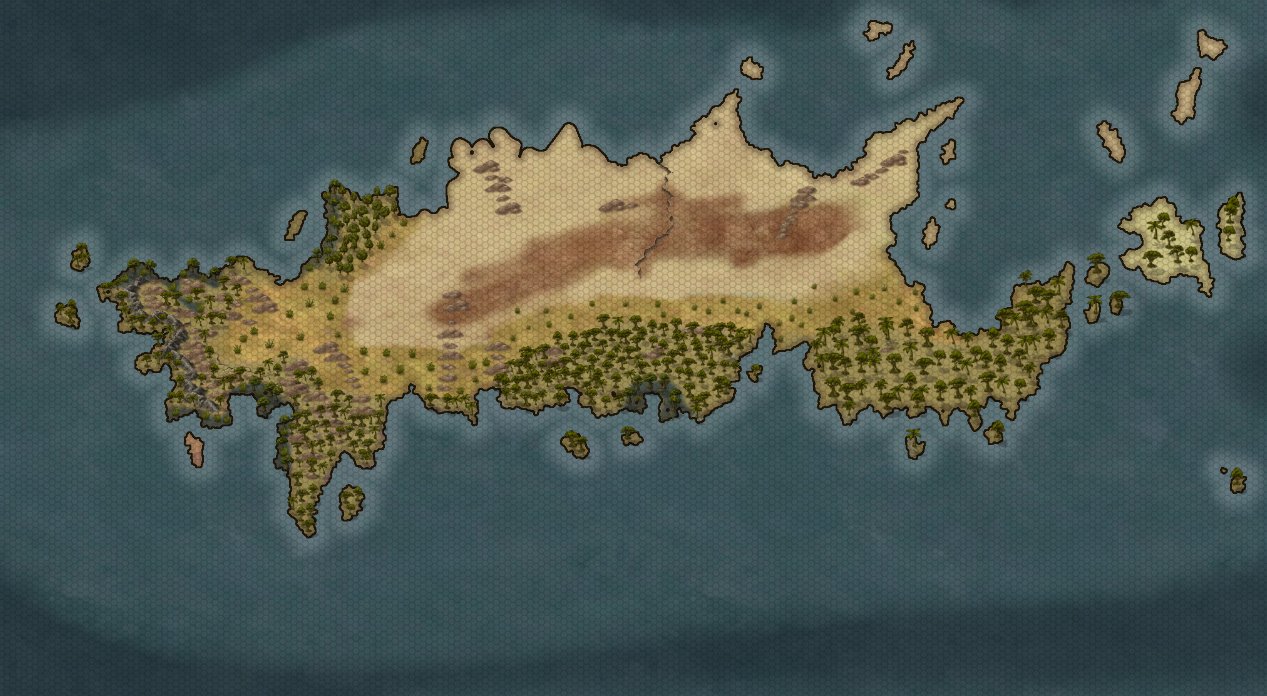

Here’s what I ended up with:

That northern desert is vast by the way – approximately two and a half times the size of the Sahara.

Rivers, lakes, and seas

For the most part, my coastline is complete, but I still need to think about lakes and rivers.

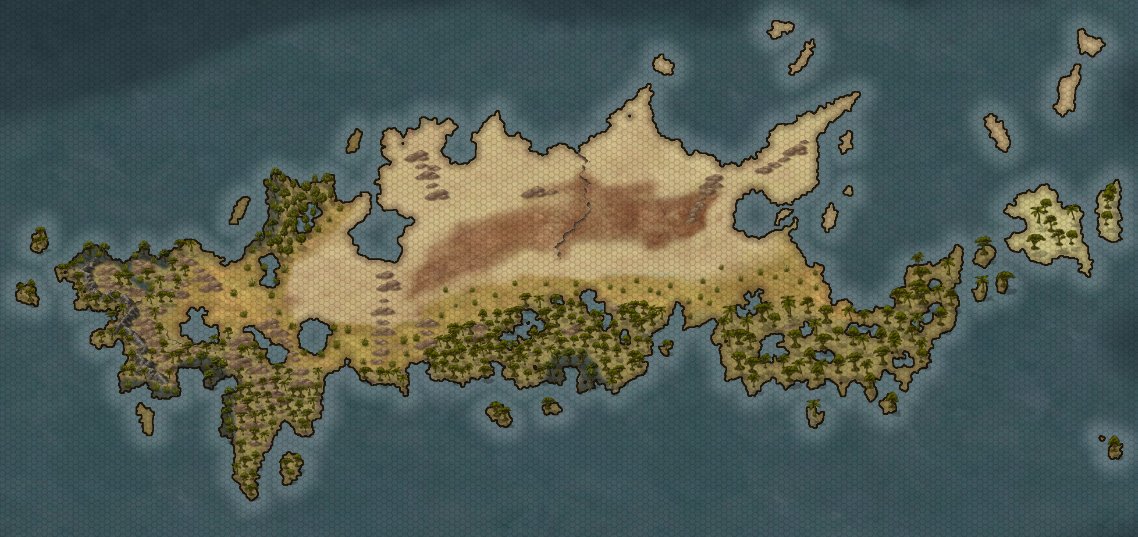

When I added terrain, I accidentally painted over the three depressions I randomly generated earlier. Oops. I will add these back in, but in the form of inland seas. (While I’m at it, I will also ‘rough up’ the northern coastline a little, as it’s looking cartoonishly rounded currently.)

I generate a few lakes for each half of the continent, too: five in the western half, twelve in the eastern. These lakes can be up to 30 hexes in size (my hexes are 50 miles) and should be concentrated in humid areas or along faults. I ended up with some fairly large lakes in the western continent, and a large number of smaller lakes in the eastern continent. The southeastern peninsula now resembles Swiss cheese.

As for major rivers, I randomly determine that there should be eleven on the western half of the continent and 20 on the eastern half. I will place these predominantly in the humid areas of the map, and ideally they should be flowing from mountains to the sea (although there aren’t many mountains on this continent). At this point, I reduced the borders of the coastline on Inkarnate, as it was difficult to make the rivers blend in. The result is below.

That’s it for Part 2. There’s not much more to do now in terms of physical geography. The next stage is human geography: settlements, roads, nations, that kind of thing. I also need to start giving some of these areas names!

If you like what I do, please subscribe by clicking here. You can unsubscribe any time. You can find me on Facebook at scrollforinitiative, Twitter @scrollforinit, and Instagram @scrollforinitiative. And if you want to make my day, you can support me on Patreon or buy me a coffee here.